KFF.org

The COVID-19 pandemic and the resulting economic recession have negatively affected many people’s mental health and created new barriers for people already suffering from mental illness and substance use disorders. In a KFF Tracking Poll conducted in mid-July, 53% of adults in the United States reported that their mental health has been negatively impacted due to worry and stress over the coronavirus. This is significantly higher than the 32% reported in March, the first time this question was included in KFF polling. Many adults are also reporting specific negative impacts on their mental health and wellbeing, such as difficulty sleeping (36%) or eating (32%), increases in alcohol consumption or substance use (12%), and worsening chronic conditions (12%), due to worry and stress over the coronavirus. As the pandemic wears on, ongoing and necessary public health measures expose many people to experiencing situations linked to poor mental health outcomes, such as isolation and job loss.

This brief explores mental health and substance use in light of the spread of coronavirus. Specifically, we discuss the implications of social distancing practices and the economic recession on mental health, as well as challenges to accessing mental health or substance use services. We draw on data on mental health prior to the COVID-19 pandemic and, where possible, include recent KFF Tracking Poll data and data from the Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey, a new survey created to capture data on health and economic impacts of the pandemic. Key takeaways include:

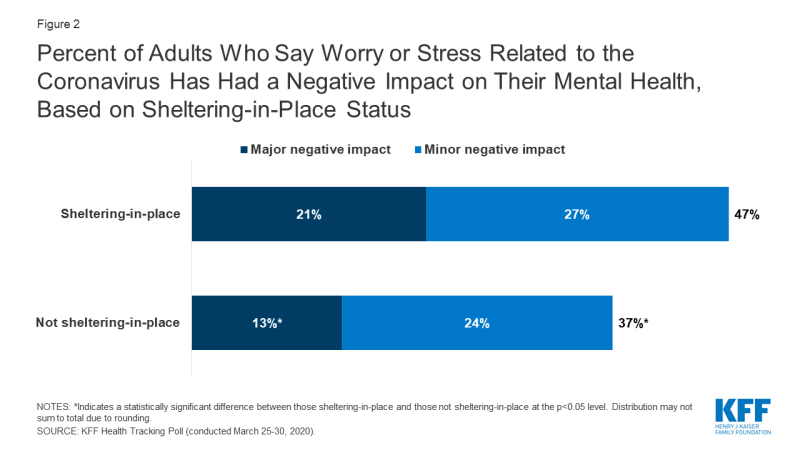

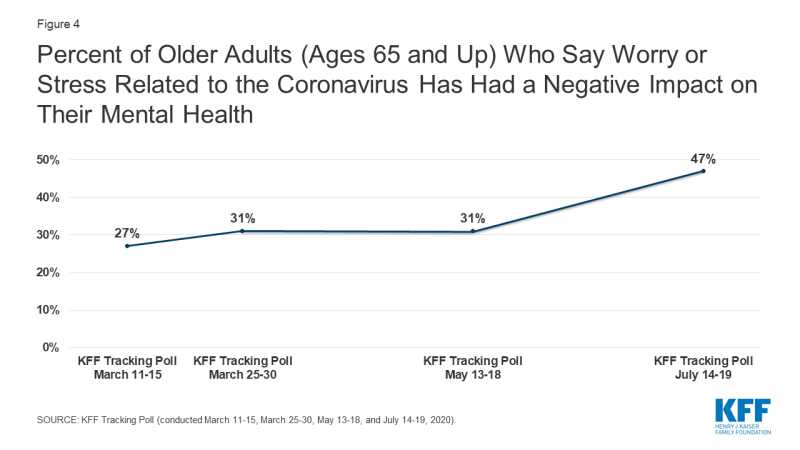

A broad body of research links social isolation and loneliness to poor mental health, and data from late March shows that significantly higher shares of people who were sheltering in place (47%) reported negative mental health effects resulting from worry or stress related to coronavirus than among those not sheltering-in-place (37%). In particular, isolation and loneliness during the pandemic may present specific mental health risks for households with adolescents and for older adults. The share of older adults (ages 65 and up) reporting negative mental health impacts has increased since March. Polling data shows that women with children under the age of 18 are more likely to report major negative mental health impacts than their male counterparts.

Research shows that job loss is associated with increased depression, anxiety, distress, and low self-esteem and may lead to higher rates of substance use disorder and suicide. Recent polling data shows that more than half of the people who lost income or employment reported negative mental health impacts from worry or stress over coronavirus; and lower income people report higher rates of major negative mental health impacts compared to higher income people.

Poor mental health due to burnout among front-line workers and increased anxiety or mental illness among those with poor physical health are also concerns. Those with mental illness and substance use disorders pre-pandemic, and those newly affected, will likely require mental health and substance use services. The pandemic spotlights both existing and new barriers to accessing mental health and substance use disorder services.

Background

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, nearly one in five of U.S. adults (47 million) reported having a mental illness in the past year, and over 11 million had a serious mental illness, which frequently results in functional impairment and limits life activities. In 2017-2018, more than 17 million adults and an additional three million adolescents had a major depressive episode in the past year.

Deaths due to drug overdose have increased more than threefold over the past 19 years (from 6.1 deaths per 100,000 people in 1999 to 20.7 deaths per 100,000 people in 2018). In 2018, over 48,000 Americans died by suicide, and in 2017-2018, nearly eleven million adults (4.3%) reported having serious thoughts of suicide in the past year.

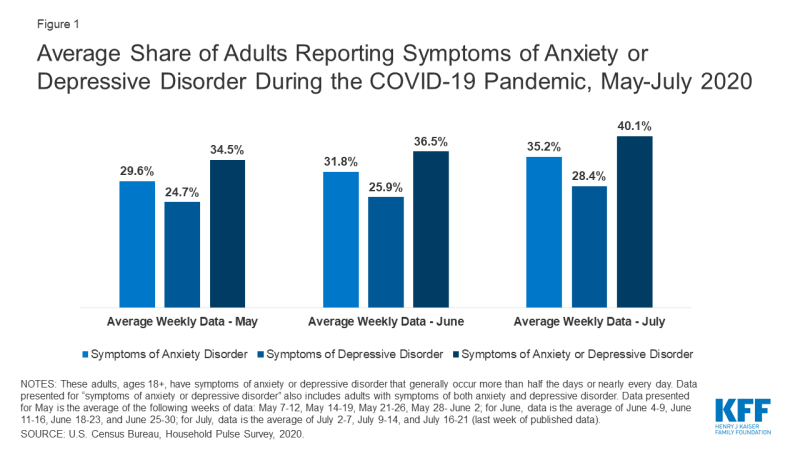

During this unprecedented time of uncertainty and fear, it is likely that mental health issues and substance use disorders among people with these conditions will be exacerbated. In addition, epidemics have been shown to induce general stress across a population and may lead to new mental health and substance use issues. More than one in three adults in the U.S. have reported symptoms of anxiety or depressive disorder during the pandemic (weekly average for May: 34.5%; weekly average for June: 36.5%; weekly average for July: 40.1%). In comparison, from January to June 2019, more than one in ten (11%) adults reported symptoms of anxiety or depressive disorder. Additionally, a recent study found that 13.3% of adults reported new or increased substance use as a way to manage stress due to the coronavirus; and 10.7% of adults reported thoughts of suicide in the past 30 days.

Figure 1: Average Share of Adults Reporting Symptoms of Anxiety or Depressive Disorder During the COVID-19 Pandemic, May-July 2020

Mental Health Risks Due to Social Isolation

As an initial response to the coronavirus crisis, most state and local governments required closures of non-essential businesses and schools and declared mandatory stay-at-home orders for all but non-essential workers, which generally included prohibiting large gatherings, requiring quarantine for travelers, and encouraging social distancing. States are now in the process of re-opening, which has been followed by many seeing a resurgence in coronavirus cases. It is unknown whether stay-at-home orders will be enforced again as spikes occur, or how long general social distancing practices will need to be encouraged.

A broad body of research links social isolation and loneliness to both poor mental and physical health. Former U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy has brought attention to the widespread experience of loneliness as a public health concern in itself, pointing to its association with reduced lifespan and greater risk of both mental and physical illnesses (Dr. Murthy serves on the KFF Board of Trustees). Additionally, studies of the psychological impact of quarantine during other disease outbreaks indicate such quarantines can lead to negative mental health outcomes. There is particular concern about suicidal ideation during this time, as isolation is a risk factor for suicide.

In the KFF Tracking Poll conducted in late March, shortly after many stay-at-home orders were issued, we found that 47% of those sheltering-in-place reported negative mental health effects resulting from worry or stress related to coronavirus (Figure 2). This rate was significantly higher than the 37% among people who were not sheltering-in-place reporting negative mental health impacts from coronavirus. Of those sheltering-in-place, 21% reported a major negative impact on their mental health from stress and worry about coronavirus, compared to 13% of those not sheltering-in-place.

Figure 2: Percent of Adults Who Say Worry or Stress Related to the Coronavirus Has Had a Negative Impact on Their Mental Health, Based on Sheltering-in-Place Status

Differing Effects of Social Isolation by Group

HOUSEHOLDS WITH CHILDREN OR ADOLESCENTS

In order to help slow the spread of coronavirus, nearly every state in the U.S. closed schools for the remainder of 2019-2020 school year, which affected 30 million students, and, subsequently, their parents or guardians. For the 2020-2021 school year, some districts have decided not to reopen campuses for in-person instruction, opting instead for online instruction. These ongoing closures could affect families beyond a disruption in their child’s education. Guidance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) regarding long-term school closures states that students depending on school services such as meal programs and physical, social, and mental health services will be impacted and that mental health issues may increase among students due to fewer opportunities to engage with peers. Data from the mid-July KFF Tracking Poll found that if schools do not reopen, 67% of parents with children ages 5-17 are worried their children will fall behind socially and emotionally.

With long-term closures of schools and childcare centers, many parents are experiencing ongoing disruption to their daily routines. KFF Tracking Polls conducted following widespread shelter-in-place orders found that over half of women with children under the age of 18 have reported negative impacts to their mental health due to worry and stress from the coronavirus. Until recently, roughly three in ten of their male counterparts reported these negative mental health impacts. In the latest, mid-July KFF Tracking poll, 49% of men with children under the age of 18 reported this negative impact on mental health.

KFF Tracking Polls have also found that, in general, women more often report negative mental health impacts due to worry and stress from the coronavirus than men (57% vs. 50%, respectively, in the mid-July KFF Tracking Poll). Similar trends by gender are seen in Household Pulse Survey findings from April to July, with women more likely to report symptoms of anxiety or depressive disorder than men over this period (44.6% vs. 37.0%, respectively, for the week of July 16-21).

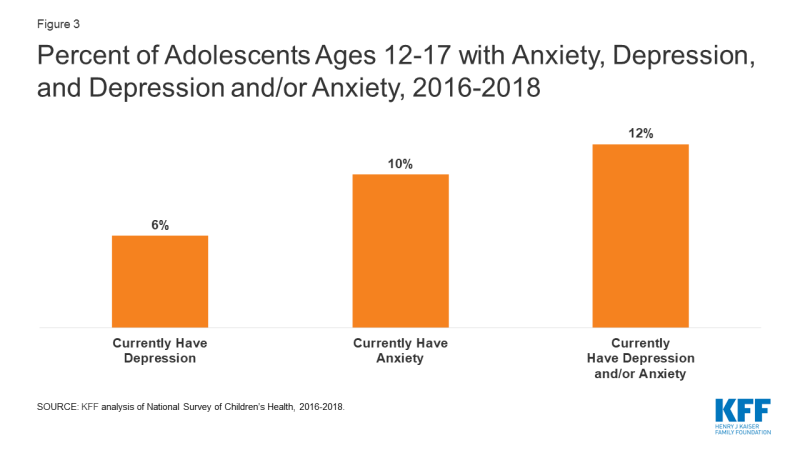

Existing mental illness among adolescents may be exacerbated by the pandemic, and with school closures, they do not have the same access to key mental health services. As shown in Figure 3, from 2016-2018, over three million (12%) adolescents ages 12 to 17, or more than one in ten, had anxiety and/or depression. Suicidal ideation is another major mental health risk among adolescents. While suicide is the tenth leading cause of deaths overall in the U.S., it is the second leading cause of deaths among adolescents ages 12 to 17. Suicidal thoughts and suicide rates among adolescents have increased over time; the crude rate of suicide deaths among adolescents was 7.0 per 100,000 in 2018 vs. 3.7 per 100,000 in 2008.5 Additionally, substance use is a concern among adolescents. Research shows that substance use among teens often occurs with other risky behaviors and can lead to substance use problems in adulthood. In 2017, more than one in ten high school students reported ever using illicit drugs (14%) or ever misusing prescription opioids (14%).

Figure 3: Percent of Adolescents Ages 12-17 with Anxiety, Depression, and Depression and/or Anxiety, 2016-2018

OLDER ADULTS

Older adults are particularly vulnerable to developing serious illness if they contract coronavirus. Many deaths due to COVID-19 have been among long-term care residents. Due to the increased vulnerability to coronavirus among older adults, it is especially important for this population to practice social distancing, among other safety measures. These measures may limit their interactions with caregivers and loved ones, which could lead to increased feelings of loneliness and anxiety, in addition to general feelings of uncertainty and fear due to the pandemic.

Data from KFF polls conducted during the pandemic show a recent increase in the share of older adults (ages 65 and up) reporting negative mental health impacts due to worry and stress from the coronavirus (Figure 4). However, older adults were less likely to report these negative mental health impacts compared to adults ages 18 to 64. Similarly, data from the Household Pulse Survey shows that, compared to younger age groups, older adults are less likely to report symptoms of anxiety or depressive disorder. However, research also shows that older adults are already at risk of poor mental health due to experiences such as loneliness and bereavement. In 2018, an estimated 27% of adults ages 65 and older reported living alone (roughly 14 out of 51 million). Older adults are particularly at-risk for depression, which is often misdiagnosed and undertreated within this population. The prevalence of depression increases for those who require home health care or are hospital patients. Suicidal ideation is a related mental health risk among older adults. In 2018, older adults accounted for nearly one out of five suicide deaths (9,102 out of 48,344) in the U.S.; more than 80% of these suicides were among males. Research shows that older, white males have the highest suicide rate in the U.S.

Figure 4: Percent of Older Adults (Ages 65 and Up) Who Say Worry or Stress Related to the Coronavirus Has Had a Negative Impact on Their Mental Health

Mental Health Risks due to Job Loss and Income Insecurity

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to millions of job losses across the country, and the U.S. officially entered an economic recession in February 2020. Although the unemployment rate in July (10.2%) was down from the pandemic’s peak unemployment rate of 14.7% in April, job gains have slowed. Research also shows that job loss is associated with increased depression, anxiety, distress, and low self-esteem; and may lead to higher rates of substance use disorder. Additionally, suicides may increase; during the Great Recession, the U.S. unemployment rate rose to 10% and was associated with increases in suicide rates.

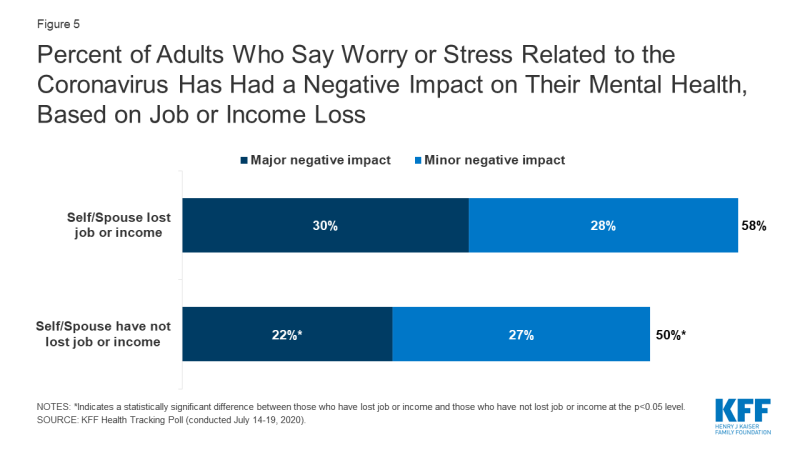

Data from recent KFF Tracking Polls found that a higher share of households that lost income or employment reported negative mental health impacts from worry or stress over the coronavirus than households that have not lost income or employment: 46% vs. 32%, respectively, in the poll conducted in mid-May; and 58% vs. 50%, respectively, in the poll conducted in mid-July (Figure 5). Separately, the KFF Tracking Poll conducted in mid-July, found that a significantly higher share of households experiencing income or job loss reported that worry or stress over the coronavirus outbreak caused them to experience at least one adverse effect, such as difficulty sleeping or eating, increases in alcohol consumption or substance use, and worsening chronic conditions, on their mental health and wellbeing compared to households with no lost income or employment (59% vs. 46%, respectively). Similarly, data from the Household Pulse Survey found that adults reporting job loss during the pandemic were more likely to report symptoms of anxiety or depressive disorder compared to adults not reporting job loss.

Figure 5: Percent of Adults Who Say Worry or Stress Related to the Coronavirus Has Had a Negative Impact on Their Mental Health, Based on Job or Income Loss

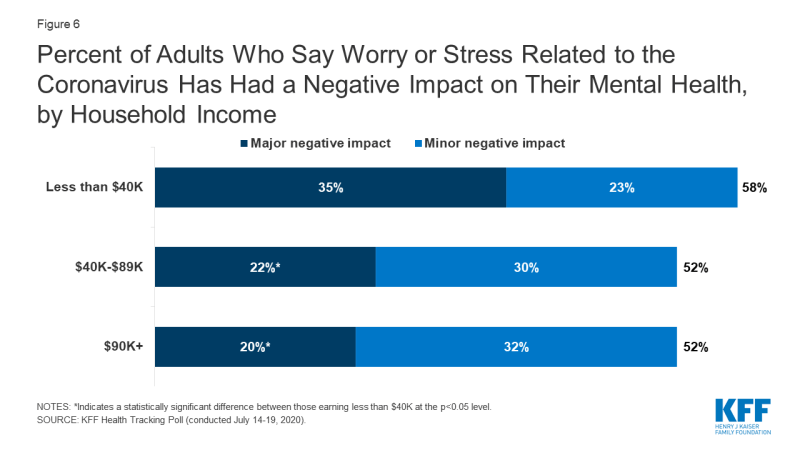

People with low incomes have generally been more likely to report major negative mental health impacts from worry or stress over coronavirus. KFF polling conducted in mid-July found that 35% of those making less than $40,000 reported experiencing a major negative mental health impact, compared to 22% of those with incomes between $40,000 to $89,999 and 20% of those making $90,000 or more (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Percent of Adults Who Say Worry or Stress Related to the Coronavirus Has Had a Negative Impact on Their Mental Health, by Household Income

Burnout and Strain Among Frontline Health Care Workers

Many hospitals across the country are overwhelmed with the increasing number of hospitalizations due to COVID-19. This has rapidly increased the demands on frontline health care workers, some of whom are also overwhelmed by supply shortages. A recent study examined the mental health outcomes of health care providers working in China during the coronavirus outbreak, finding that providers reported feelings of depression, anxiety, and overall psychological burden. This experience was particularly acute among nurses, women, and providers directly involved in diagnosing and treating patients with COVID-19.

Research indicates that burnout in hospitals is particularly high for young registered nurses and nurses in hospitals with lower nurse-to-patient densities. Physicians are also prone to experiencing burnout and can consequently suffer from mental health issues, including depression and substance use. The risk of suicide is also high among physicians.

The KFF Tracking Poll conducted in mid-April found that 64% of households with a health care worker said worry and stress over the coronavirus caused them to experience at least one adverse effect, such as difficulty sleeping or eating, increases in alcohol consumption or substance use, and worsening chronic conditions, on their mental health and wellbeing, compared to 56% of the total population. KFF Tracking Polls conducted during the pandemic have not found a significant difference in negative mental health impacts for households with a health care worker compared to households without a health care worker.

Mental Health Risks Associated with Poor Physical Health

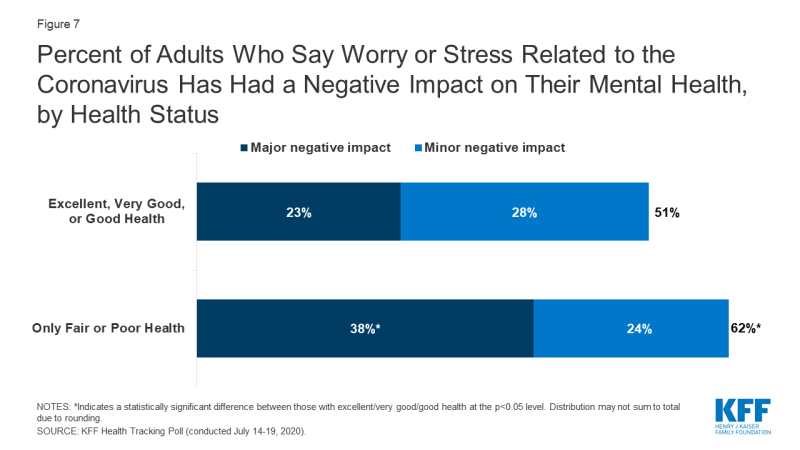

According to the CDC, people who have chronic illnesses such as chronic lung disease, asthma, serious heart conditions, and diabetes are among those with a high risk of severe illness from COVID-19. Research shows that mental health disorders are common comorbidities among patients with these and other chronic illnesses. KFF Tracking Polls conducted since April found that adults with fair or poor health status were more likely to report negative mental health impacts due to worry or stress related to the coronavirus compared to adults with excellent, very good, or good health status. As shown in Figure 7, 62% of adults with fair or poor health status reported negative mental health impacts compared to 51% of adults with excellent, very good, or good health status. A large share of those with fair or poor health status reported major negative health impacts (38%).

Figure 7: Percent of Adults Who Say Worry or Stress Related to the Coronavirus Has Had a Negative Impact on Their Mental Health, by Health Status

Discussion

In recognition of the mental health implications of the COVID-19 pandemic, the World Health Organization released a list of considerations to address the mental well-being of the general population and specific, high-risk groups, and the United Nations put forth recommendations for addressing and minimizing poor mental health outcomes, including incorporating mental health in national COVID-19 responses and increasing access to mental health care through telemedicine. The CDC has also shared information and recommendations regarding stress and coping in its online COVID-19 resources. Additionally, the National Institute on Drug Abuse has noted that while little is known about COVID-19 in relation to substance use, there are potential associations between severe COVID-19 and substance use disorder. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) has also provided resources and recommendations to address mental health and substance use disorders during the pandemic.

The pandemic is likely to have both long- and short-term implications for mental health and substance use, particularly for groups likely at risk of new or exacerbated mental health struggles. An analysis of the psychological toll on health care providers during outbreaks found that psychological distress can last up to three years after an outbreak. As the emotional toll and burnout among health care providers in the U.S. has already become more pronounced, several response efforts have been established. Governor Cuomo of New York, one of the hardest hit states, recently announced plans to expand mental health services across the state for frontline health care workers. This includes launching an emotional support hotline and requiring health insurers to waive out-of-pocket costs for in-network mental health care. Another high-risk group facing potential long-term mental health impacts are those experiencing job loss and income insecurity. An analysis by Well Being Trust and the Robert Graham Center for Policy Studies projects that based on the economic downturn, an additional 75,000 deaths due to suicide and alcohol or drug misuse may occur by 2029.

Those with mental illness and substance use disorders pre-pandemic, and those newly affected, will likely require mental health and substance use services. Consequently, the pandemic spotlights both existing and new barriers to accessing mental health and substance use disorder services. Among households that report skipping or delaying health care during the pandemic, 4% state that as a result, their or a family member’s mental health condition worsened. Access to needed care was a concern prior to the pandemic. In 2018, among the 6.5 million nonelderly adults experiencing serious psychological distress, 44% reported seeing a mental health professional in the past year. Compared to adults without serious psychological distress, adults with serious psychological distress were more likely to be uninsured (20% vs 13%) and be unable to afford mental health care or counseling (21% vs 3%). For people with insurance coverage, an increasingly common barrier to accessing mental health care is a lack of in-network options for mental health and substance use care. Those who are uninsured already face paying the full price for these and other health services. As unemployment continues to increase and people lose job-based coverage, some may regain coverage through options such as Medicaid, COBRA, or the ACA Marketplace, but others may remain uninsured.

Limited access to mental health care and substance use treatment is in part due to a current shortage of mental health professionals, which will likely be exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Since the start of the pandemic, there has been an increase in mental health services provided via telemedicine. The federal government and many states governments have expanded coverage of telemedicine and relaxed certain regulations to alleviate the impact of business closures and social distancing on access to needed care.

The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (CARES Act) may help to address the likely increased need for mental health and substance use services. It includes a $425 million appropriation for use by SAMHSA, in addition to several provisions aimed at expanding coverage for, and availability of, telehealth and other remote care for those covered by Medicare, private insurance, and other federally-funded programs. It also allows for the Secretary of the Department of Veterans Affairs to arrange expansion of mental health services to isolated veterans via telehealth or other remote care services. These provisions may alleviate some of the acute need for remote mental health and substance use services. In addition, the CARES Act extends the duration of, and expands, Medicaid Community Mental Health demonstrations, which are currently underway as part of efforts to increase care access and quality at community behavioral health clinics.

As policymakers continue to discuss further actions to alleviate the burdens of the COVID-19 pandemic, the increased need for mental health and substance use services could continue longer term even as new cases and deaths due to the novel coronavirus subside.