What may be the most important development in American religion and politics over the last few decades is the growing emergence of the “God gap” — the contrasting religiosity between Republican and Democrat voters. This reflects how the parties have seemingly polarized on matters of religion.

The Republicans portray themselves as the party of conservative morality and family values, while Democrats have increasingly become the party of the nonreligious or those who hold to progressive religious values on culture war issues. Media outlets have tended to focus on the ascendance of the religious right and the electoral importance of groups like White evangelicals when it comes to covering religion and politics in the United States.

But that laser-like focus on conservative religious groups has led to a backlash by some reporters and scholars. Recently, there has been a notable effort to try and focus on those who use religious belief as a motivation to fight for liberal political causes like health care for all and amnesty for those who entered the United States illegally. In recent years, books like “American Prophets” by Jack Jenkins and “Just Faith” by Guthrie Graves-Fitzsimmons have highlighted the work of many of these leaders and groups around the United States.

But, despite these and other efforts to convince the American public that the religious left is a potent force in American politics, the data just does not support that assertion. In fact, it shows that Democrats are significantly less religious by any objective measure of the term compared to their Republican counterparts.

“Democrats are significantly less religious by any objective measure of the term compared to their Republican counterparts.” - Ryan Burge

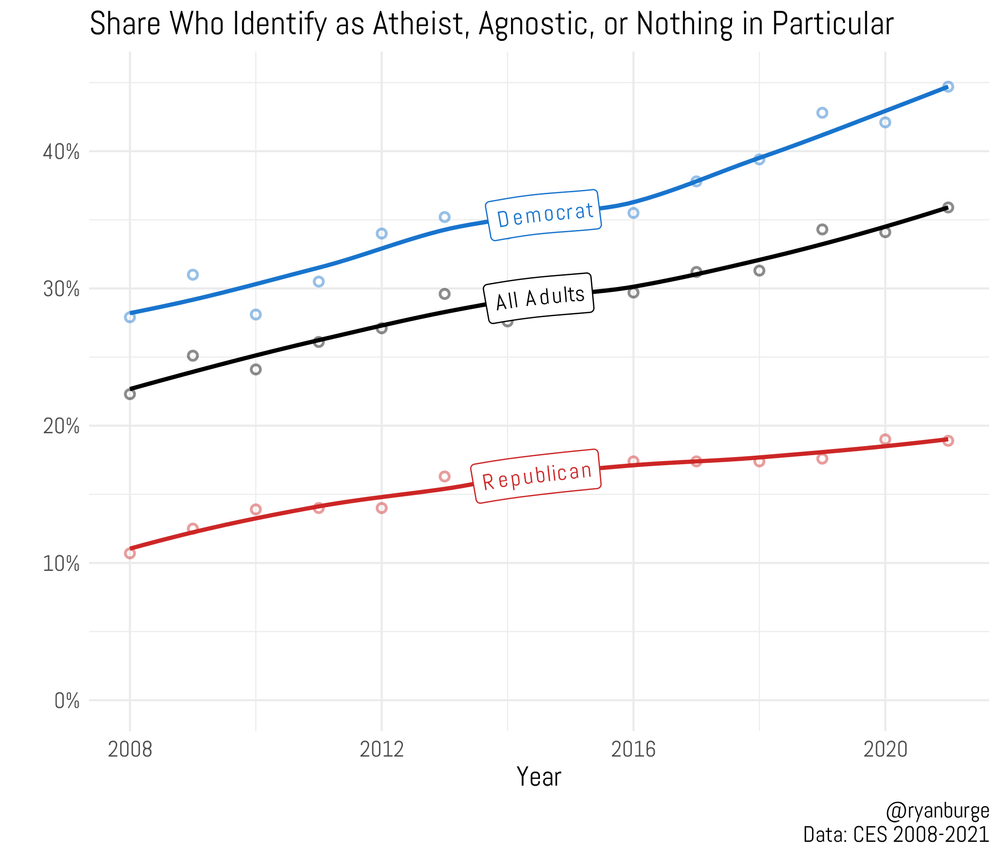

For instance, members of the Democratic Party are significantly more likely to report that they are atheist, agnostic, or have no religion in particular compared to those who align with the GOP. In 2008, about 12% of Republicans claimed no religious affiliation compared to 28% of Democrats. That gap has not narrowed in any significant way in the last thirteen years. In 2021, about 45% of Democrats said that they were nones — it was just 19% of Republicans.

It seems very probable that in the next two election cycles that the majority of Democrats who enter the voting booth will claim that they have no religious affiliation, a sentiment shared by less than 1 in 4 Republicans. This phenomenon is not new, as Hout and Fischer noted two decades ago that politics were already driving people out of churches, but the fact that the trend has only accelerated is what may be worth more reflection.

Thus, there’s clear evidence that from a religious affiliation standpoint, the Democrats, by and large, are much less attached to religion than Republicans. However, it would be unfair to assume that Democrats who are still aligned with a faith tradition engage in less religious behavior than Republicans who are still attached to religion. To compare apples to apples, I excluded from the sample anyone who identified as atheist, agnostic, or nothing in particular. If anything, this should be a boost to the Democrats' religiosity, because their sample has been nearly cut in half, while about 80% of Republicans are still included. But, even with this concession, the same conclusion remains — Democrats are less religious than Republicans.

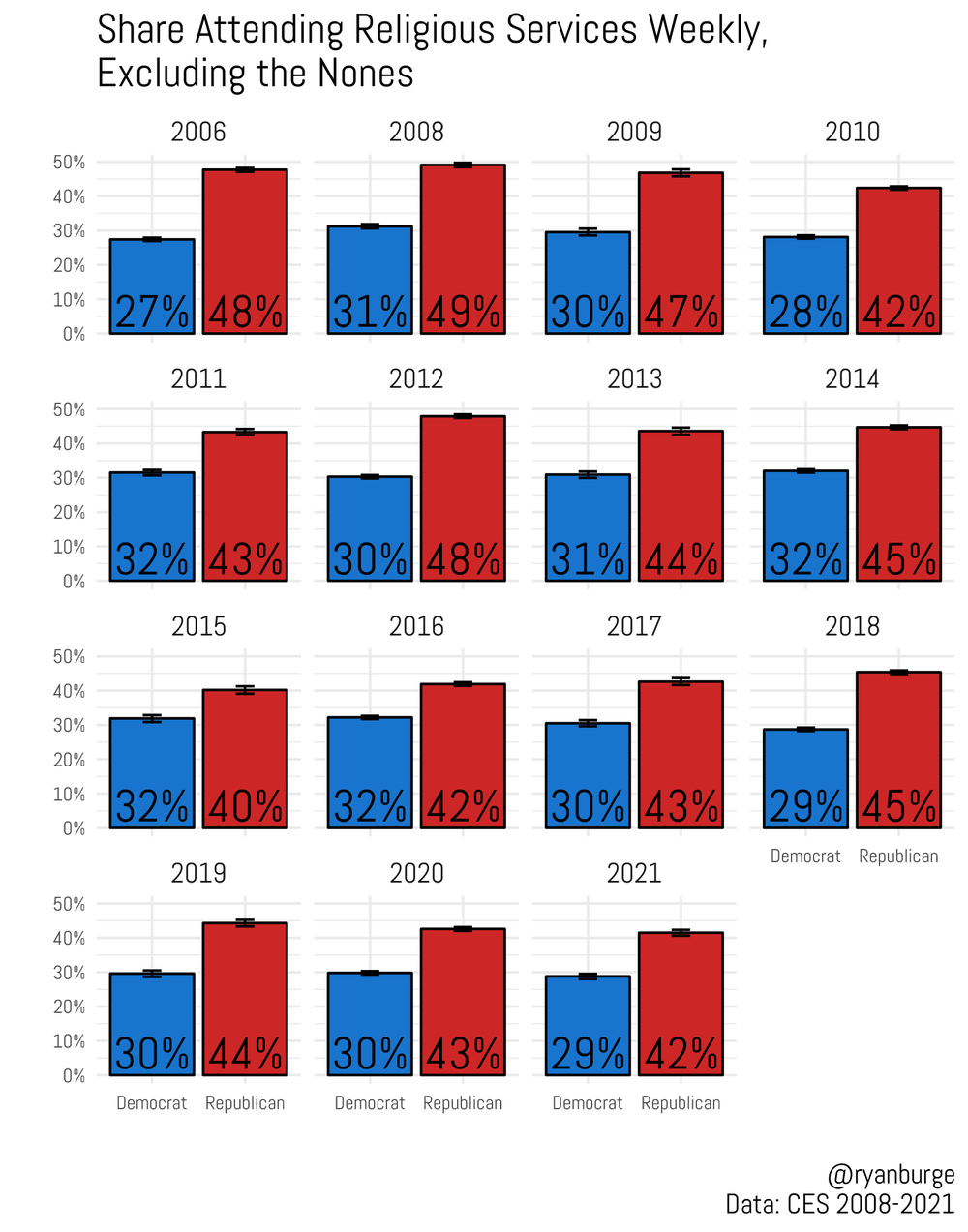

One of the ways that religion is often operationalized is through the lens of religious service attendance. I calculated the share of Democrats and Republicans who reported attending services at least once a week in 15 years of the Cooperative Election Study, and the results again point to the same conclusion — Democrats are less religiously active than their Republican counterparts.

It is staggering how large the gaps are in many years. For instance, when Barack Obama was elected president in 2008, nearly half of Republicans indicated they attended services weekly compared to just 31% of Democrats. In fact, in the 15 survey waves analyzed here, the gap in weekly attendance is at least 10 percentage points in 14 of those years included in the analysis. It is worth pointing out that Republican service attendance has declined more noticeably than the Democrats over the last decade, but the religious attendance gap still persists.

However, there may be very good reasons that Democrats are attending religious services less than Republicans — they don’t feel welcome at churches that are increasingly becoming more conservative. There have been several significant studies in political science that have come to that conclusion in the last five years. Thus, maybe religious Democrats just don’t feel like they fit into a local religious congregation and have altered their attendance to avoid uncomfortable situations.

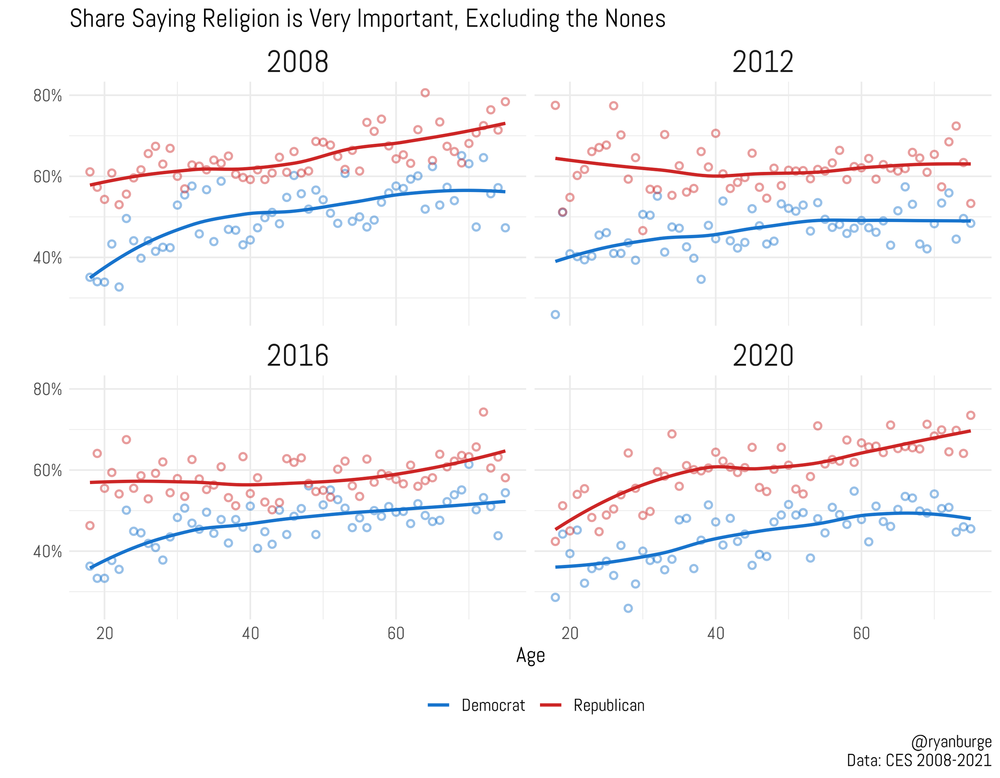

To sidestep that possibility, I calculated the share of Democrats and Republicans who said that religion was “very important” to them by age in the last four presidential election years. And, again, there’s a clear God gap emerging even when the nones are excluded from the sample. Republicans, regardless of age, are more likely to say that religion is very important to them compared to Democrats.

In 2008, about 60% of younger Republicans said religion was very important — it was less than half of young Democrats. In 2012, the gap between Republicans and Democrats was largely unaffected by age: About 60% of Republicans said religion was very important — it was about 50% of Democrats. While the gap did narrow a bit in the 2016 data to slightly less than 10 points, it then widened again in the 2020 presidential election year.

Looked at in totality, it’s hard to review these data points and conclude anything other than Democrats are less religious — by any measure, including frequency of prayer — compared to those who align with the GOP. Democrats are more likely to indicate that they have no religious affiliation, but even when those nones are removed from both samples, Republicans are more likely to report weekly attendance and to indicate that religion is very important to them.

Why might this be happening? Stratos Patrikios argued that it’s because the American public perceives a close connection between evangelical Protestants and the Republican Party, and thus many assume that to be a Democrat is to be less religious. Thus, Democrats believe that saying religion is very important is “acting Republican.” This is an intriguing possibility that will need more empirical work to support.

While social science is not prepared to fully explain these findings, they no doubt have important societal implications for the United States. If religion is now inextricably linked with the GOP, then the overall religiosity of the average American is tied to the electoral fortunes of the Republican Party. If the Democrats are increasingly being seen as the party of the nonreligious, it seems likely that younger generations will see no future in which they can be religious devout but also progressive in their political orientations. That will leave the United States polarized not just on political lines but religious ones as well.