This is a story about when big innovations happen.

Not how, but when. And to some extent, why.

Hopefully you find it counterintuitive at first before it quickly seems obvious. That’s how most important ideas work.

And hopefully you’ll see why this period, for all the hell its brought, could be the new beginnings of something promising.

Cars and airplanes are two of the biggest innovations of modern times.

But there’s an interesting thing about their early years.

Few looked at early cars and said, “Oh, there’s a thing I can commute to work in.”

Few saw a plane and said, “Ah-ha, I can use that to get to my next vacation.”

It took years and decades for people to see that potential.

What they did say early on was, “Can we mount a machine gun on that? Can we drop bombs out of it?”

Every new invention looks like a toy at first. Adolphus Greely was one of the first people outside the car industry to realize the “horseless carriage” could be useful.

Greely, a brigadier general, purchased three cars in 1899 – almost a decade before Ford’s Model T – for the U.S. Army to experiment with. In one of its first mentions of automobiles, The Los Angeles Times wrote about General Greely’s purchase:

It can be used for the transportation of light artillery such as machine guns. It can be utilized for the carrying of equipment, ammunition and supplies; for taking the wounded to the rear, and, in general, for most of the purposes to which the power of mules and horses is now applied.

Nine years later, the LA Times did an interview with young brothers Wilbur and Orville Wright, who talked about the prospects of their new flying machine:

The Wrights had reason to believe this was true. Their only real customer in their early years – the only group to show interest in airplanes – was the U.S. Army, which purchased the first “flyer” in 1908.

The Army’s early interest in cars and planes wasn’t a fluke of lucky foresight. Go down the list of big innovations, and militaries show up repeatedly.

Radar.

Atomic energy.

The internet.

Microprocessors.

Jets.

Rockets.

Antibiotics.

Interstate highways.

Helicopters.

GPS.

Digital photography.

Microwave ovens.

Synthetic rubber.

They all either came directly from, or were heavily influenced by, the military.

Why?

Are militaries home to the greatest technical visionaries? The most talented engineers?

Perhaps.

But more importantly they’re home to Really Big Problems That Need to Be Solved Right Now.

Innovation is driven by incentives. And incentives come in many forms.

On one hand there’s, “If I don’t figure this out I might get fired.” That will get your brain in gear.

Then there’s, “If I figure this out I might help people and make a lot of money.” That will produce creative sparks.

Then there’s what militaries have dealt with: “If we don’t figure this out right now we’re all going to die and the world will be taken over by Adolf Hitler.” That will fuel the most incredible problem-solving and innovation in the shortest period of time that the world has ever seen.

The 1955 book The Big Change describes the burst of scientific progress that took place during World War II:

What the government, through its Office of Scientific Research and Development and other agencies, was constantly saying during the war was, in effect: “Is this discovery or that one of any possible war value? If so, then develop it and put it to use, and darn the expense!”

The result has been likened to a team of experts combing through a deskful of scientific papers, pulling out those which gave promise of usefulness, and then commandeering all the talent and appropriating all the money that might be needed to translate formulae into goods.

Militaries are engines of innovation because they occasionally deal with problems so important – so urgent, so vital – that money and manpower are removed as obstacles, and those involved collaborate in ways that are hard to emulate during calm times.

You cannot compare the incentives of Mountain View coders trying to get you to click on ads to Manhattan Project physicists trying to end a war that threatened the country’s existence. You can’t even compare their capabilities. The same people with the same intelligence have wildly different potential under different circumstances.

Militaries are an extreme example of panic-induced innovation.

A broader point that applies to everyone is that the biggest innovations rarely occur when everyone’s happy and safe, or when the future looks bright. They happen when people are a little panicked, worried, and when the consequences of not acting quickly are too painful to bear.

That’s when the magic happens.

The 1930s were a disaster.

Almost a quarter of Americans were out of work in 1932. The stock market fell 89%.

Those two economic stories dominate the decade’s attention, and they should.

But there’s another story about the 1930s that rarely gets mentioned: It was, by far, the most productive and technologically progressive decade in history.

The number of problems people solved, and the ways they discovered how to build stuff more efficiently, is a forgotten story of the ‘30s that helps explain a lot of why the rest of the 20th century was so prosperous.

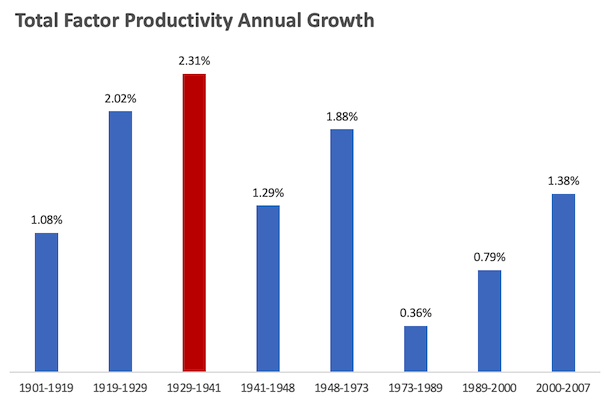

Here are the numbers: Measuring total factor productivity – that’s economic output relative to the number of hours people worked and the amount of money invested in the economy – hit levels not seen before or since:

Economist Alex Field writes:

In 1941, the U.S. economy produced almost 40 percent more output than it had in 1929, with virtually no increase in labor hours or private-sector capital input. Almost all of the increase in output per hour is attributable to technological and organizational advance [of the 1930s].

A couple of things happened during this period that are worth paying attention to, because they explain why this happened when it did.

The New Deal’s goal was to keep people employed at any cost. But it did a few things that, perhaps unforeseen, become long-term economic fuels.

Take cars. The 1920s were the era of the automobile. The number of cars on the road in America jumped from one million in 1912 to 29 million by 1929.

But roads were a different story. Cars were sold in the 1920s faster than roads were built. A new car’s novelty was amazing, but its usefulness was limited.

That changed in the 1930s when road construction, driven by the New Deal’s Public Works Administration, took off.

Spending on road construction went from 2% of GDP in 1920 to over 6% in 1933 (vs. less than 1% today). The Department of Highway Transportation tells a story of how quickly projects began:

Construction began on August 5, 1933, in Utah on the first highway project under the act. By August 1934, 16,330 miles of new roadway projects were completed.

Historian Robert Grodon writes:

The 1930s witnessed the construction of multilane engineering marvels, including the George Washington, Golden Gate, and Bay Bridges, as well as the beginning of multilane limited-access turnpikes, including the Merritt Parkway in southern Connecticut and the first section of the Pennsylvania Turnpike. These anticipated, and in some cases became part of, the postwar Interstate Highway System. As of 1940, a map of the principal routes of the U.S. highway system looks virtually identical to a map of today’s Interstate Highway System, except that most of the roads were two-lane with intersections rather than featuring limited access.

The Pennsylvania Turnpike, as one example, cut travel times between Pittsburgh and Harrisburg by 70%. The Golden Gate Bridge opened up Marin County, which had previously been accessible from San Francisco by ferry boat.

Multiply those kinds of leaps across the nation and 1930s was the decade that transportation truly blossomed in the United States. It was the last link that made the century-old railroad network truly efficient, creating last-mile service that connected the world. A huge economic boon.

Electrification also surged in the 1930s, particularly to rural Americans left out of the urban electrification of the 1920s. The New Deal’s Rural Electrification Administration brought power to farms in what may have been the decade’s only positive development in regions that were economically devastated. The number of rural American homes with electricity rose from less than 10% in 1935 to nearly 50% by 1945.

It is hard to fathom, but it was not long ago – during some of our lifetimes and most of our grandparents’ – that a substantial portion of America was literally dark. Franklin Roosevelt said during a speech on the REA:

Electricity is no longer a luxury. It is a definite necessity. It lights our homes, our places of work and our streets. It turns the wheels of most of our transportation and our factories. In our homes it serves not only for light, but it can become the willing servant of the family in countless ways. It can relieve the drudgery of the housewife and lift the great burden off the shoulders of the hardworking farmer.

I say “can become” because we are most certainly backward in the use of electricity in our American homes and on our farms. In Canada the average home uses twice as much electric power per family as we do in the United States.

Electricity becoming a “willing servant,” – introducing washing machines, vacuum cleaners, and refrigerators – freed up hours of household labor in a way that let female workforce participation rise. It’s a trend that lasted more than half a century and is a key driver of both 20th century growth and gender equality.

A second productivity surge of the 1930s came from everyday people forced by necessity to find more bang for their buck.

The first supermarket opened in 1930. The traditional way of purchasing food was to walk from your butcher, who served you from behind a counter, to the bakery, who served you from behind a counter, to a produce stand, who took your order. Combining everything under one roof and making customers pick it from the shelves themselves was a way to make the economics of selling food work during a time when a quarter of the nation was unemployed.

Laundrymats were also invented in the 1930s after sales of individual washing machines fell – they marketed themselves as washing machine rentals.

Factories of all kinds looked at bludgeoned sales and said, “What must we do to survive?” The answer was often to build the kind of assembly line Henry Ford introduced to the world in the previous decade.

Output per hour in factories had grown 21% during the 1920s. “During the Depression decade of 1930-1940 – when many plants were shut down or working part time” historian Frederick Lewis Allen writes, “there was intense pressure for efficiency and economy – it had increased by an amazing 41 per cent.”

He wrote again in 1943:

Anybody can understand the basic principle of a fork truck. But the layman can only stand in awe before some of the complex electronic machines which came into use after 1935 – machines for measuring materials with microscopic exactitude, or for watching the performance of a machine and automatically correcting flaws in its performance. The language used by engineers in talking about them is quite unintelligible to him, as are the processes involved. But at least he can appreciate the miraculous results they achieve.

Something as simple as quality control sampling massively reduced manufacturing waste and became common in the 1930s. Lewis Allen again:

The workman can thereupon regulate the adjustment of his machine, not by guesswork, but with exact knowledge of just how it is functioning. This [process] – which in many a factory has saved large amounts of money by reducing the number of defective products – has the effect of raising the status of the workman by making him in a special sense his own boss, the informed critic and judge of his performance.

This story was repeated across industries. Productivity growth in the 1930s was not constrained to a few fields, like it was in the 1920s when manufacturing accounted for nearly all the gains. The ‘30s saw huge technical progress in utilities, farming, wholesale trade, retail, transportation, mining, and communication.

“The trauma of the Great Depression did not slow down the American invention machine,” Alex Field writes. “If anything, the pace of innovation picked up.”

Economist David Henderson writes:

“Topping” techniques in electricity generation — using exhaust steam from high-pressure boilers to heat lower-pressure boilers — raised capacity by 40 to 90 percent with virtually no increase in the cost of fuel or labor.

New treatments increased the life of railroad ties “from eight to twenty years.”

With new paints, the time for paint to dry on cars fell from three weeks (!) to a few hours.

[Total research and development] employment in 1940 was 27,777, up from 10,918 in 1933.

Driving knowledge work in the ‘30s was the fact that more young people stayed in school because they had nothing else to do. High school graduation surged during the depression to levels not seen again until the 1960s, according to Field. One student recalled:

High schools had a larger attendance than ever before, especially in the upper grades, because there were few jobs to tempt anyone away. Likewise college graduates who could afford to go on to graduate school were continuing their studies – after a hopeless hunt for jobs – rather than be idle.

All of this – the better factories, the new ideas, the educated workers – became vital in 1941 when America entered the war and became the Allied manufacturing engine.

The big question is whether the big technical leap of the 1930s could have happened without the devastation of the depression. And I think the answer is “no” – at least not to the extent that it occurred.

You could never push through something like the New Deal without an economy so wrecked that people were desperate to try anything to fix it.

It’s doubtful that business owners and entrepreneurs would have so urgently found new efficiencies without the record threat of business failure.

Managers looking at their employees and saying, “Go try something new. Blow Up the playbook, I don’t care,” is not something that gets said when the economy is booming and the outlook is bright.

Big, fast, changes only happen when they’re forced by necessity.

World War II began on horseback in 1939 and ended with nuclear fission in 1945. NASA was created in 1958 two weeks after the Soviets launched Sputnik and landed on the moon just 11 years later. Stuff like that rarely happens that fast without fear as a motivator.

It reminds me of this:

HOBBES: Do you have an idea for your story yet?

CALVIN: You can’t just turn on creativity like a faucet. You have to be in the right mood.

HOBBES: What mood would that be?

CALVIN: Last-minute panic.

There’s an obvious limit to stress-induced innovation.

There’s a delicate balance between the economy being thrown upside down, everyone inside it driven into action by necessary panic, while the foundations of the economy itself remain intact, capable of supporting the new ideas and innovations.

My guess is that balance has only happened a few times in modern history.

One was the period from 1930 to 1945. Parts of the Cold War might qualify, though it was concentrated in a few defense sectors.

The hardest thing about stress-induced innovation is reconciling that positive long-term trends can be born when people are suffering the most. It makes the topic difficult to even discuss without looking insensitive.

But think of what’s happening in biotech right now. Many have pessimistically noted that the fastest a vaccine has ever been created is four years. But we’ve also never had a new virus genome sequenced and published online within days of discovering it, like we did with Covid-19. We’ve never built seven vaccine manufacturing plants when we know six of them won’t be needed, because we want to make sure one of them can be operational as soon as possible for whatever kind of vaccine we happen to discover. We’ve never had so many biotech companies drop everything to find a solution to one virus. It’s as close to a Manhattan Project as we’ve seen since the 1940s.

And what could come from that besides a Covid vaccine?

New medical discoveries? New manufacturing and distribution methods? Newfound respect for science and medicine?

So many important discoveries happen by accident when frantic experimentation uncovers an unrelated quirk of science. In his book How We Got to Now, Steven Johnson writes:

Innovations usually begin life with an attempt to solve a specific problem, but once they get into circulation, they end up triggering other changes that would have been extremely difficult to predict … An innovation, or cluster of innovations, in one field ends up triggering changes that seem to belong to a different domain altogether.

This is happening in medicine right now. It’s happening with doctors in hospitals and scientists in labs. It’s impossible to know what it will lead to. But there’s currently so much experimentation, with stakes so high, that you know we’re going to look back in 10 or 20 years at the important discoveries that wouldn’t have been possible without Covid-19. That’s always how it’s worked.

Or think about cities.

I don’t think San Francisco or New York are dead – that’s absurd. But it doesn’t take many companies letting their employees work remotely to take the pressure off one of the biggest social problems of the last generation: affordable housing.

Having so much of the economy’s economic potential clustered in a few cities – a few neighborhoods, really – created $2 million starter homes in cities with good jobs and cheap homes in cities with little economic growth. Even a slight shift to permanent remote work could make cities more livable and rural areas more prosperous.

Or colleges. Student loans are another major social issue of the last generation. Without Covid the college industry would have likely corrected in the coming decades. With Covid it’s correcting in the coming weeks.

When schools say, “Pay full tuition and we’ll teach you over Zoom,” and students and parents say, “Wait, there’s no way that’s worth it,” you realize – quickly, in stark terms – that you’re not paying for an education. You’re paying for a credential and a social experience, which doesn’t need to cost $68,000 a year.

Scott Galloway recently put it:

There’s a recognition that education — the value, the price, the product — has fundamentally shifted. The value of education has been substantially degraded. There’s the education certification and then there’s the experience part of college. The experience part of it is down to zero, and the education part has been dramatically reduced. You get a degree that, over time, will be reduced in value as we realize it’s not the same to be a graduate of a liberal-arts college if you never went to campus. You can see already how students and their parents are responding.

It’s not crazy to say that could be the most important developments of the next generation, because student loans have been one of the biggest burdens of the past generation.

On the tech front, Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella said “two years of digital transformation took place in two months,” this spring.

What does that lead to?

Almost every business in the world is now asking how they can work more efficiently, save a few bucks here and here, and do more of their business online.

What does that lead to?

Tens of millions of people who lost their jobs, and hundreds of millions of people who kept theirs but worried, will be permanently scarred into thinking about risk, opportunity, and safety nets differently than they were six months ago.

What does that lead to?

I don’t think anyone knows the answers.

All we know is that the most important changes of the last 100 years have taken place during upheavals. And we’re currently in the biggest upheaval of the last 100 years.

We know that creativity and discovery surge when people are forced to find, rather than just want, new solutions.

We know that an irony of technology is that economies often make their greatest leaps forward when the outlook is bleakest.

It might be one of the only silver linings of 2020.

In October, 1933 an Ohio lawyer named Benjamin Roth wrote a diary entry about the economic carnage devastating his town. A quarter of the town was unemployed. Farms were bankrupt. Surviving businesses used new efficiencies to get by with fewer workers, exacerbating unemployment.

Roth tried to remain optimistic.

“I am confident that new inventions and scientific discoveries will remedy this situation,” he wrote.

At nearly the same time he was writing an electrical engineer named Edwin Armstrong introduced a new radio technology to David Sarnoff, an RCA executive struggling to hold together an industry smashed by the Depression.

Sarnoff later recalled the conversation, as told in the book Man of High Fidelity:

“Why are you pushing this so hard?” asked Sarnoff.

“There is a depression on,” said Armstrong. “The radio industry needs something to put life in it. I think this is it.”

The technology – FM radio – transformed 20th century communication.

Maybe we’ll be so lucky.

BI-SIYATA DISHMAYA!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

The Collaborative Fund blog